The CDC reported in 2016 that obesity affected about 93.3 million US adults, or 40 percent of the adult population, and trend is worsening. The Harvard School of Public Health projects the obesity rate will rise to around 50 percent by 2030. In all, 72 precent (yes, nearly three-quarters) of the adult population is either overweight or obese. This has made weight loss a very big business.

The number of active dieters in the US is estimated at 97 million, and the total US weight loss industry hit a new peak of $72 billion in 2018, according to MarketResearch.com. Clearly, the desire for weight loss is widespread.

But those aren’t the only expenses. The CDC estimated the cost of obesity at $147 billion In 2008. A decade later, it’s surely higher.

With obesity reaching epidemic proportions, many have surely wondered if the problem is hereditary. Could obesity be passed down from parent to child? The CDC has answered that question: “Genetic changes in human populations occur too slowly to be responsible for the obesity epidemic.”

However, overweight and obese parents may pass on to their children the habits of physical inactivity and the tendency to eat high-calorie, processed foods. Conversely, active, healthy eaters may also pass on these same positive tendencies to their children.

Scientists are still learning about fat and not all of it is bad. At its core, body fat (aka, adipose tissue), is comprised of cells, just like everything else in your body.

It was once believed that adults could not create new fat cells. However, researchers have shown that adults constantly produce new fat cells, regardless of their body-weight status, sex or age.

Though the number of fat cells in a person’s body increases through childhood and adolescence, it remains fairly constant throughout your adult life, regardless of whether or not you diet or are thin or fat, say researchers at the Karolinska Institute, Sweden.

However, the scientists found that we continually create new fat cells (aka, adipocytes) to replace those that break down and die. Yes, when fat cells die, as all cells do, the body simply creates new ones in its effort to keep the number constant. About 10 percent of adipocytes die each year and they are replaced at the same rate.

The scientists at the Karolinska Institute found that obese people produce approximately twice as many new fat cells annually as lean people. They also found that fat cell death in obese people happens at twice the rate as lean people.

Other studies have shown that obese and overweight individuals have a greater number of fat cells than “naturally thin” people. When we slim down, fat cells shrink in size, but the total number of fat cells does not decrease. So, an obese person who loses weight will still have more fat cells than the person who never gained weight. The greater number of fat cells in formerly obese people may be a factor in their tendency to regain the weight they lost.

When we gain weight, we store the extra lipids we don’t use in our fat cells, which makes them grow in size. As we lose weight, these cells shrink, but they never disappear. Weight loss is attributed to fat cells shrinking, not losing them entirely.

Though excess body fat increases the risk of developing heart disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, stroke, osteoarthritis and certain cancers, not all body fat is the same.

Brown fat helps to maintain your body temperature and is activated when you get cold. While white fat stores calories, brown fat contains many more mitochondria (cellular engines), which burn calories to produce heat. In fact, brown fat even burns calories from white fat. The mitochondria in brown fat provide its color. Though brown and white fat cells are often mixed in together in fat tissue, white fat is much more prevalent.

Researchers have found that people with lower body mass indexes (BMIs) tend to have more brown fat. There is also evidence that brown fat activity declines with age, which may cause people to gain weight as they grow older, aside from the natural decline in muscle mass that lowers metabolic rate.

Additionally, researchers believe that exercise may stimulate hormones that activate brown fat, and that spending time in the cold may also cause the growth of new brown-fat cells.

It is believed that brown fat is activated and proliferates in response to overfeeding (aka, consuming too many calories). Since it takes energy to digest food, calorie burning usually increases at mealtimes. However, studies in humans have shown dramatic differences between individuals in the energy cost of overfeeding. These studies have shown that individuals with similar dietary intake and exercise patterns exhibit dramatic differences in their tendency to gain weight.

Researchers are looking into whether increasing the amount of brown fat could be a safe and effective therapy to limit obesity.

Though body fat is often viewed as our enemy, it has many useful purposes, such as: storing energy, storing fat-soluble vitamins (A, E, D and K), keeping us warm (fat is an insulator), and providing padding around our organs that protects us from physical trauma.

Clearly, some body-fat is necessary, even vital. The problem is that too many Americans have too much of it — sometimes far too much — to be healthy.

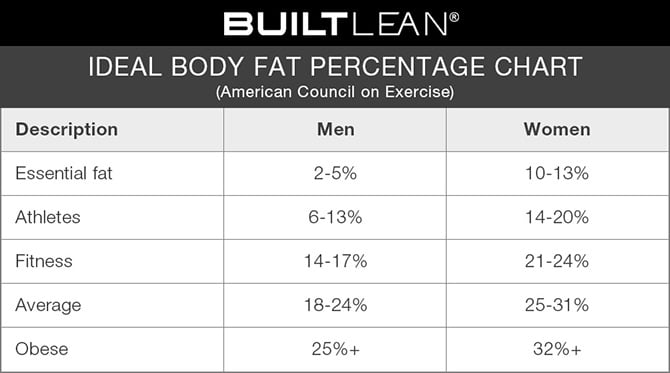

To determine healthy body-fat percentage ranges, based on your fitness level, follow these guidelines:

Eat well. Get in Motion. Stay in Motion.