Our breath is the fundamental element of our life.

Most people can comfortably hold their breath for 30 to 60 seconds. Some can safely hold it for as long 2 minutes. However, permanent brain damage usually begins after only 4 minutes without oxygen, and death can occur as soon as 4 to 6 minutes after that.

Obviously, our breath is vital. Yet, we’re rarely conscious of it. Breathing is part of the autonomic nervous system, meaning that it is automatic and unconscious. The autonomic nervous system has two primary branches: The sympathetic nervous system and the parasympathetic nervous system.

The sympathetic nervous system prepares the body for the “fight or flight” response during any potential danger. On the other hand, the parasympathetic nervous system inhibits the body from overworking and restores it to a calm and composed state. So, we can think of the sympathetic nervous system as the gas pedal and the parasympathetic nervous system as the brake pedal.

The breath is really the quickest and most efficient way to affect and control the nervous system. By extending the exhalation longer than the inhalation, you generate parasympathetic activation and often a soothing, calming, steadying effect. This natural phenomenon is called respiratory sinus arrhythmia. As you exhale, the vagus nerve will slow down the heartbeat.

So, consciously slowing your breath can ease the parasympathetic nervous system, which can slow your heart rate and promote feelings of calm.

Studies have found that breathing practices can help reduce symptoms associated with anxiety, insomnia, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and attention deficit disorder (ADD).

Normal respiration rates for adults at rest range from 12 to 16 breaths per minute, according to Johns Hopkins. It should be noted that 12 breaths per minute amounts to one breath every 5 seconds. Exceeding 12 breaths per minute is a sign of quick and shallow breathing.

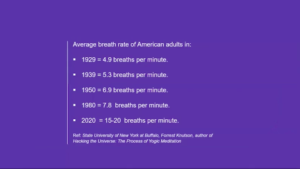

Unfortunately, we breathe a lot faster than previous generations did, and it’s really not good for us. Most American adults now breathe at a rate of 15-20 per minute. Yet, any breath rate above 12 per minute activates the sympathetic nervous system (fight or flight). This means that most of us are in a constant state of fight or flight activation simply due to the way we breathe.

Scientists are finding that breathing at the rate of about six exhalations per minute can be especially restorative, triggering a relaxation response in the brain and body. Some people can reduce their respiratory rate to this level using slow, mindful breathing techniques.

There is a direct relationship between respiration rate and heart rate. Exhalation – particularly when sustained longer than inhalation – slows your heart. Meanwhile, inhalation accelerates your heart. And the more your heart beats, the more respiration occurs. As the heart beats faster, it uses more energy and sends more oxygen to the body. For example, during exercise the respiratory rate will increase to about 40–60 breaths per minute.

Breathing with your mouth, especially when you’re not exercising vigorously, is a sign of dysfunctional breathing.

Nose breathing is more beneficial than mouth breathing, which is unnatural. Breathing through your nose can help filter out dust and allergens, boost your oxygen uptake, and humidify the air you inhale. Mouth breathing, on the other hand, can dry out your mouth, which may increase your risk of bad breath and gum inflammation.

The nose produces nitric oxide, which improves your lungs’ ability to absorb oxygen. Nitric oxide also increases your ability to transport oxygen throughout your body, including inside your heart. It relaxes vascular smooth muscle and allows blood vessels to dilate.

Nitric oxide is also antifungal, antiviral, antiparasitic, and antibacterial. Simply put, it helps the immune system fight infections.

It is also believed that you absorb oxygen around 15 percent better when you exhale through your nose when compared to mouth breathing.

So, breathing with your nose is preferable in many ways. Meanwhile, mouth breathing, as previously stated, is a sign of dysfunctional breathing.

Inhaling with your chest is another common sign of dysfunctional breathing. If you notice that your chest is the first thing to move when you begin inhaling, it’s a sign that you’re engaging in shallow, upper chest breathing.

A shallow or a quick breathing pattern is a sign that your diaphragmatic muscles may not be actively stabilizing your trunk, which can lead to poor posture and instability in your low back.

Poor diaphragmatic control can cause the muscles in your chest and the front of your shoulders to become short and tight. If you find yourself slouching your head or shoulders forward, this can be a sign that you’re not activating your diaphragm when you breathe.

You should be able to limit shoulder movement while breathing, keeping the shoulders from elevating. Elevating your shoulders when breathing causes upper chest breathing.

Tight neck, chest, and shoulder muscles can cause shallow breathing. If you carry lots of tension in your shoulders and neck, this can be a sign that you engage in stressed and shallow breathing.

Practice contracting your abdominal muscles as you breathe. Using your abdominals (part of your core) can help you breathe better. You should feel your abdominal muscles moving in and out as you breathe.

A healthy breathing pattern allows your body to maintain a high metabolism and deliver oxygen to vital tissues. Shallow breathing increases both blood pressure and heart rate. In addition, if you breathe too fast or don’t inhale deeply enough, you can increase the pH of your blood, which can decrease the amount of blood getting to your brain and muscles, and result in less oxygen being released by the blood. This can make you feel tired and fatigued.

So, though we typically take breathing for granted and pay little, if any, attention to it (unless we’re exercising), it really is a critical and fundamental element to good health and lower stress levels.

The fact that slow, measured breathing can slow heart rate, promote feelings of calm, and help reduce symptoms associated with anxiety, insomnia, PTSD, depression, and ADD is all the reason we need to begin a regular, deliberate practice. Begin with the following:

1. While standing or sitting, draw your elbows back slightly to allow your chest to expand.

2. Take a deep inhalation through your nose for a count of four.

3. Retain/hold your breath for a count of four.

4. Using your belly muscles, exhale through your nose for a count of eight.

5. Continue to breath like this for 2-5 minutes. See if you can eventually work your way up to 10 minutes.

Utilizing this method should bring your breathing down to a rate of about six exhalations per minute, which scientists are finding to be especially restorative, triggering a relaxation response in the brain and body.

Another useful technique is alternate nostril breathing, known as pranayama in India. This yogic technique also promotes relaxation and lowers heart rate.

Alternate nostril breathing is best practiced on an empty stomach. Avoid the practice if you’re feeling sick or congested. Keep your breath smooth and even throughout the practice.

1. Choose a comfortable seated position.

2. After an exhale, use your right thumb to gently close your right nostril.

3. Inhale through your left nostril and then close your left nostril with your middle or index finger.

4. Release your thumb and exhale out through your right nostril.

5. Inhale through your right nostril and then close this nostril.

6. Release your finger to open your left nostril and exhale through this side.

7. This is one cycle.

8. Continue this breathing pattern for up to 5 minutes.

9. Finish your session with an exhale on the left side.

You can utilize these techniques any time you’re feeling stressed or anxious throughout the day. Try them both, or least one, every day. Naturally, you should discontinue these practices if you experience any feelings of discomfort or agitation.